A Myth as a Primary Source?!

- inthearchivespodca

- Nov 13, 2024

- 4 min read

A myth as a primary source would be illogical, after all a myth is nothing more than a glorified fairytale—a story made up by its creator. It is a fictious story, therefore it cannot be considered as a primary source. Seton Hall University defines a primary source as a first-hand account of an event or topic, and it is the most direct evidence of an event. Primary sources are written down by eye witnesses; they are not retellings of an old story such as myths. Yet, creation myths break the status quo of the criteria by becoming a primary source. Creation myths are completely different from regular myths such as the Iliad and Odyssey. But, how could this be?

A creation myth is a narrative that describes the original order of the universe. Creation myths tell the story of how a certain culture perceives the creation of the world. These myths often serve to explain the world through symbolic or narrative language. For example, many creation myths use the natural world, plants, celestial bodies, etc. to explain creation. Many Native American creation myths symbolize water as a method of purification, transformation, and the flow of life. Symbolic language is frequently employed to explain various aspects of the world in numerous myths. Each creation myth is presented in a narrative format and is intended for oral storytelling. These stories often serve as a way to explain the origins of the world and humanity's place in it.

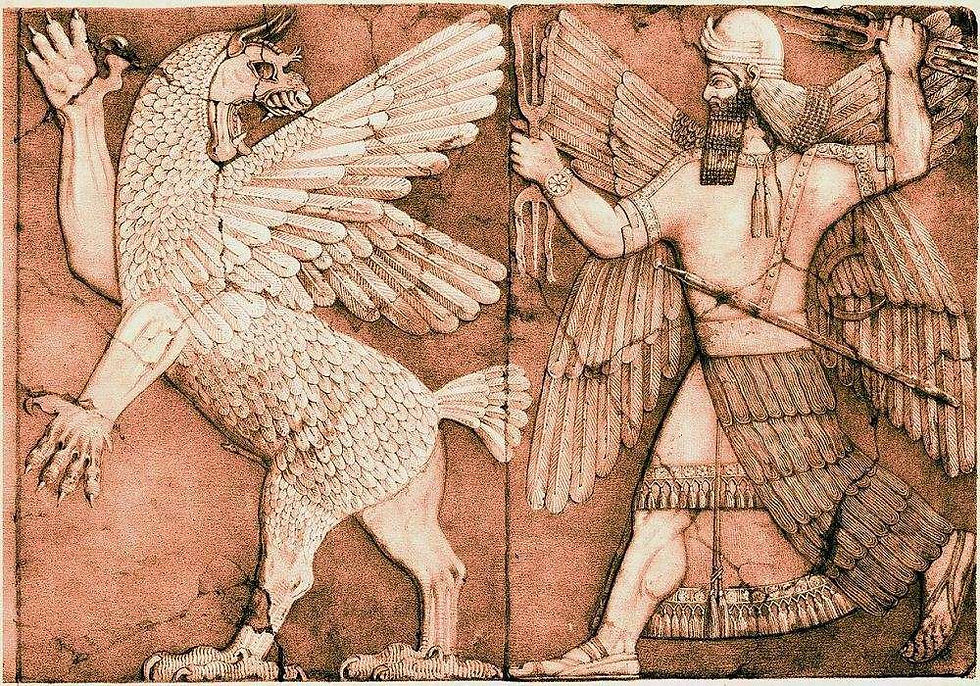

The most popular creation myth is the Babylonian Enuma Elish, named after its opening line, "When on high." As one of the oldest creation myths in the world, Enuma Elish holds a significant place in ancient mythology. The story begins with nothingness and chaos, and then the gods come together to create the universe. The seven tablets that comprised Enuma Elish were discovered where Nineveh once stood in the year 1800. The tablets date back to c. 1200 BCE, and it is written in Sumero- Akkadian Cuneiform. In addition to telling the story of creation, it also shares the story of the Babylonians' most important god, Marduk. The Seven Tablets of Creation (another name for Enuma Elish) have helped historians understand the Babylonians' worldview and culture. For these reasons, creation myths are considered primary sources.

Creation myths are important in understanding a cultural group’s origins and religious practices. The story tells us something about a culture. For many cultures, these myths are their first-hand account of creation which they pass down orally from one generation to the next, until it is eventually written down. Because creation myths are believed to be first-hand accounts it is considered a primary source; however, just because it is a primary source does not make a creation myth any truer. After all, a myth is still a myth.

Creation myths are not scientific and should not be taken literally, yet their significance lies within their own culture. In general, myths are viewed as a reflection of a culture's essence, with creation myths encapsulating the essence of a culture. These stories explain cultural practices. Robin Kimmerer states, “Creation stories offer a glimpse into the worldview of a people, of how they understand themselves, their place in the world, and the ideals to which they aspire.”[1] Creation myths show the worldview of a people and can often tell us more about a culture than artifacts, which are primary sources. It tells us how religious practices and traditions came into existence. Take, for example, the natives that inhabited Hispaniola, the Taino, and their religious practices. The Taino worshiped in caves because they believed life began in the caves. Fray Ramon Pané, a Spanish Friar, recorded the Taino myth of creation. He states, “There is a region of that island which is called Caunana, where they say humankind first issued from grottos in two mountains, that is, the greater part from the larger cave, and the lesser part from the smaller cave…”[2] For the Taino people life began in a cave, and therefore caves are considered sacred places of worship. Pané states that their most religious site is a cave called Ivanaboina. They believe that the sun and moon “issued forth” from that cave, and that is why it is considered one of their most sacred sites. A reading and understanding of a creation myth explains the cultural and religious practices of any culture that has a creation myth. It gives historians and anthropologists new insights on why a culture acts the way it does, or why it believes what it believes.

Creation myths provide valuable first-hand insight into the culture of an ancient civilization or native tribe. These myths reveal much about their identity, offering important insights into the origins of their religious practices. As primary sources, creation myths serve as first-hand accounts of a culture's worldview, making them essential documents for studying how ancient cultures saw and understood the world.

Discover different creation stories online:

Check out the In the Archives podcast for the Taino Creation Myth

For African Creation myths Click here.

For Native American Creation myths Click here.

For Enuma Elish Click here.

Bibliography

“Seton Hall University Libraries: Primary Sources - An Introductory Guide: What Is a Primary Source?” What is a Primary Source? - Primary Sources - An Introductory Guide - Seton Hall University Libraries at Seton Hall University. Accessed October 14, 2024. https://library.shu.edu/primarysources#:~:text=A%20primary%20source%20is%20a,not%20been%20modified%20by%20interpretation.

Lambert, Wilfred G.. Babylonian Creation Myths. United States: Penn State University Press, 2013.

Long, C. H.. "creation myth." Encyclopedia Britannica, August 23, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/topic/creation-myth.

Mark, Joshua J. “Enuma Elish - the Babylonian Epic of Creation - Full Text.” World History Encyclopedia, December 6, 2022. https://www.worldhistory.org/article/225/enuma-elish---the-babylonian-epic-of-creation---fu/.

Pané, Ramón. “On Taino Religious Practices.” In Reading the American Past: Selected Historical Documents, Vol. 1, edited by Michael P. Johnson, 2-4. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2012.

[1] Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants. Milkweed Editions. 16 September 2013. p. 305.

[2] Ramón Pané, “On Taino Religious Practices,” in Reading the American Past: Selected Historical Documents, Vol. 1, ed. Michael P. Johnson (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2012) 2.

Comments